Solidity. That is the message the IRT Powerhouse conveyed to someone who was very much in need of it during the spring of 1994, the very first times I walked near this mammoth building on Eleventh Avenue. Its massiveness, solidity, strength, and grace were awe-striking to a single person standing before it on the full block it takes up between 11th Avenue from West 58th to West 59th streets. I first encountered the building after moving into the Hell’s Kitchen neighborhood in 1994 and loved walking the far west blocks and then-gritty mid-50s waterfront. Reading up on it yielded discoveries of its history: This powerhouse was the place that, starting in 1904, first supplied electricity to New York City’s new subway system that connected people from Brooklyn through Manhattan to the Bronx.

As the years progressed, the IRT Powerhouse became even more meaningful, with a committed group of citizens who fought for its preservation as a New York City landmark. Mind you, this was no white elephant – it still serves as a ConEdison steam and electric generation plant. In 2018, the Landmarks Preservation Commission designated the IRT Powerhouse as a landmark. A place like the powerhouse can remind us of the city’s spirit, enterprise, and determination to look to the future and of the great labor that it took for workers to construct such a humongous building.

People experience historic places in both individual and group ways, and their meanings change over time. Since the turn of the year from 2019 to 2020, the world has been dealing with a devastating and difficult global pandemic that is exacting a deadly toll. Meantime, large protests in the streets and public places, grief, and demands for action have shook the United States, in response to the heinous killing of a black man, George Floyd, by a police officer who held a knee on his neck, suffocating him, while Floyd lay for 8 minutes and 46 seconds, at times pleading, “I can’t breathe.” Three other policemen abetted Floyd’s death by standing by.

Protests and marches, the vast majority peaceful, are happening daily, marked by demands for an end to the systemic racism and structural injustice and inequality that have killed so many black and brown people for centuries – without accountability – and deprived millions systematically of liberty, freedom, and opportunity. We have come to know so many names – too many lost to mothers and fathers – Eric Garner, Trayvon Martin, Michael Brown, Philadro Castile, Ahmaud Arbery, Breonna Taylor, Tamir Rice, and others who were killed in encounters with police or targeted with violence due to their skin color.

Cut Off from Places

At such times, historic places and sites that we preserve hold meanings for each generation. This spring has been different, as we seek to look to history. Spring has always held a bountiful slate of tours, events, programs, and activities at these places or opportunities to walk historic neighborhoods and honor the preservation of them. Throughout May, people each year have commemorated Historic Preservation Month in the United States, and events continue into June. However, this year the pandemic has for months halted people gathering and cut us off from each other in a lot of ways.

Those working in preservation understand that this is the very time we need to connect with our past and each other, draw on our roots, and learn from and affirm sustaining values. Preservation, after all, is not about places or landmarks frozen in time. These sites and neighborhoods hold continuous stories of struggle, fights for freedom and rights, expressions, progress, inspiration, resilience, and triumph. We comprehend more from experiencing them. Moreover, the work to preserve other places does not let up.

If anything, the shutdowns across the United States and world have inspired more care and effort to connect virtually. Many are inventive and creative, some quirky, some inviting a dig deep and others quick visits. In that spirit, here is a selection of virtual explorations and preservation activities, plus places that we can help preserve for future generations. Like the looking and walking near a building, a burial ground, a meeting place, a town or city square, a shoreline, or a neighborhood, a virtual experience offers a quieting of the mind, a contemplation of values, and an affirmation for the soul in this tumultuous time. Some are fun or intriguing, while others offer a bracing acknowledgment of a dark episode in America’s history.

Far from Her Sharecropping Beginnings

It has been 47 years since the first Preservation commemoration began in the U.S., as Preservation Week, in 1973. The National Trust for Historic Preservation played a foundational role in advocating its beginning. For its outreach this May, in the middle of the pandemic, the National Trust created a Virtual Preservation Month program of varied digital experiences, unlocking one each day, and they remain online.

Tour Madam C.J. Walker’s estate. Madam C.J. Walker’s life journey is one of rising from growing up a child in a family of Louisiana sharecroppers to becoming a success in her own international beauty business. In the process, she became a role model for countless African-American women and a philanthropist and activist who fought against lynching and for African-American soldiers returning from World War I. She was one of the first African-American millionaires in the United States, and the first woman to be a self-made millionaire.

Her Hudson Valley summer home estate is a landmark. While the estate, located in Irvington, is not open to the public, you can take a virtual tour of it and find out more about her life. Walker’s great-great granddaughter, A’Lelia Bundles, narrates the tour, which shows the elegant furnishings and palatial exterior, and describes activities there, like the gathering of some 100 black and progressive white activists at the mansion’s opening party. One can sense the beauty and peace of this estate even while strolling online.

Villa Lewaro, the estate of Madam C.J. Walker

Photo: Jim Henderson / CC BY 4.0

See the performance of a `Blues Poem.’ Bunk Johnson’s name likely will never roll off the tongue like other jazz greats, but he had a key impact on New Orleans jazz in the first half of the 20th century. Johnson (born circa 1880) was a jazz trumpeter who played with legends such as Jelly Roll Morton and Louie Armstrong. His temperamental, sometimes-destructive ways and boasting sparked plenty of controversy during his lifetime. However, he was a central figure in the revival of New Orleans jazz in the 1940s, after making an amazing career comeback.

Bunk Johnson and Lead Belly, playing with Bunk Johnson’s band in 1946

Photo: William P. Gottlieb Collection, Library of Congress

The National Trust honors Johnson’s life and work through an opportunity to virtually visit a Louisiana historic house and garden and listen to a one-act performance, “Bunk Johnson – Out of the Shadows: A Blues Poem.” It takes place at the Shadows-on-the-Teche, a National Trust historic site in New Iberia, La., that was part of a sugar cane plantation. Theater artist and novelist Ifa Bayeza wrote the play, which chronicles Johnson’s life and place in jazz history, with support from the National Trust’s African American Cultural Heritage Action Fund.

Sample pickles as history. Mankind has loved pickles for many centuries and in many cultures. In the U.S., this food opens a window into immigrant experience in the late 19th and early 20th centuries. In April, the Tenement Museum had planned a program featuring this delicious, well-loved food as history. The shutdown due to COVID-19 preluded museum visitors from enjoying this event in person. However, the Tenement Museum produced a virtual program, and it is part of the National Trust activities, via YouTube. The video showcases the important tradition and business of Eastern European Jewish immigrants making and selling pickles, and it closes with a demo of how to make your own cucumber pickles.

A pickle vendor on a city street

Discover a Civil Rights and Social Justice Map of Greenwich Village. The protests that have erupted nationwide ask us to look deeply into the mirror that is America and face stark truths about the systematic racism and intolerance that has been and remains a deep wound. We gain deep strength and perspective by looking at sites and neighborhoods where the struggle has taken place in each generation to ensure the U.S. would live up to its promise of equality and human rights. Greenwich Village has been referred to as ground zero for many of the campaigns for justice and for its historic place as a center of arts and culture flourishing at the intersections and edges of race, gender, class, ethnic background, and sexuality. The Greenwich Village Society of Historic Preservation provides a splendid way to experience it.

Even when not walking the streets of Greenwich Village, you can grasp, block by block, the important history and culture that have taken place here, through the GVSHP’s Civil Rights and Social Justice Map. It encompasses African-American, Women’s, Hispanic, Asian-American, and LGBTQ history.

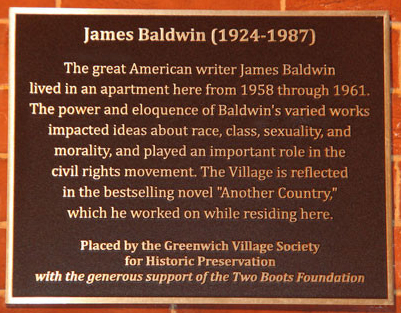

Here are just several highlights, among dozens. At 70 Fifth Avenue, the NAACP had its headquarters from 1914 to the mid-1920s and made significant history, campaigning for federal anti-lynching legislation and against President Woodrow Wilson’s establishment of segregation in the federal workforce. The GVSHP is campaigning for landmark designation for this 12-story, Beaux Arts building. At 81 Horatio Street, writer James Baldwin lived during the late 1950s and early 1960s, and he did some of his most prolific writing during his time in the Village. The roots of civil. rights struggles run very deep and long in Greenwich Village, as indicated by a few addresses that were sites of African Free Schools, which provided education to free and enslaved black children in the early 19th century.

The plaque at 81 Horatio Street, where James Baldwin lived for a time

Photo: Greenwich Village Society of Historic Preservation

The GVSHP map proves how much history lies under our feet and around us if we only look. The map is just one layer of the society’s content and documentation of landmarks and historic places, such as blog posts, oral histories, archival collections of photos and other images, podcasts, videos, and landmark reports.

See how Chinese-American immigrants worked for equal rights and better lives. So often, the stops on the map and preservation records reveal lesser-known stories and events from history. Many know that Chinese-Americans faced discrimination and violence during the later half of the 19th century, but do not how they dealt with the rife prejudices.

Take in, through this GVSHP essay, three sites where organizations and activists provided support to Chinese Americans. At a building that housed the Chinese Consulate (later demolished) during the 1880s and 1890s, the immigrants found lodging on upper floors. In another building that survives until today, at 23 St. Mark’s Place, the Chinese Guild, founded in 1889, served hundreds of members of the Chinese-American community with various legal, social welfare, and educational needs. The Guild provided English lessons, organized a choir, and helping individuals in court cases stemming from attacks and vandalism on their laundries by a group of white laundry-owners, among other initiatives. An important milestone happened at Cooper Union in the East Village, where a group of U.S. citizens and non-citizen Chinese merchants met to form the Chinese Equal Rights League and battle the immigration restrictions of the period.

Cooper Union, 1899

Photo: Museum of the City of New York Digital Collection

Understand the painful history of the Tulsa Race Massacre. As demonstrations and protests have filled the streets, many delve into events that happened generations ago to further understand how racist violence has long dogged this nation’s history and to grasp the long-overdue need for real equality and justice. This week, on May 31 and June 1, was the 99th anniversary of the Tulsa Race Massacre, when a mob of white residents looted and burned down the prosperous African-American neighborhood of Greenwood. It is one of the most horrifying chapters of racial violence in American history, one that for too long was neglected.

Historians, historic preservationists, and others are seeking to continually bring this history to wider knowledge and examine its ramifications nearly a century later. The Tulsa Historical Society has an in-depth online exhibit about the Tulsa Race Massacre. This 18-hour spasm of violence erupted after an incident involving the arrest of an African-American man. Police had arrested the man, Dick Rowland, after an incident involving a white woman, Sarah Page, in the elevator of an office building. Following an inflammatory report in the Tulsa Tribune, tensions became inflamed and mobs of white and African-American men gathered around the courthouse, where some fired shots. The African-American men retreated to the Greenwood neighborhood.

The situation quickly worsened. Hour by hour, hysteria grew, fueled by a false belief that black citizens were organizing an uprising. In the early morning hours, thousands of white residents rushed into the Greenwood neighborhood and set many fires and looted properties. Called out by the governor, the National Guard helped firemen put out the fires and took thousands of African-American residents into custody. Once the situation quieted, some 35 city blocks lay in ruins, as the Tulsa Historical Society exhibit details. While the exact toll is not known, it is estimated that as many as 300 African-American residents died.

The Tulsa Historical Society’s online exhibit contains vivid, shocking photos and other images; documents such as the Red Cross reports, newspaper clippings, and records of civil suits that the African-American Tulsans later filed; and audio recordings of survivors and contemporaries. For further examination, resources include links to archives and a recommended reading list. In a large gallery, photos show the Greenwood neighborhood engulfed in fire and smoke; bodies of victims lying in the streets; a portrait of an author who wrote a firsthand account of the disaster, in 1922; and detained residents walking through the area. It is all unsettling to absorb.

Fires left the Greenwood neighborhood in utter ruin.

It was an event of widespread devastation, followed by a resolve by the African-American community in Tulsa to reestablish the neighborhood, despite hostility from many white residents. Within the decade, they rebuilt a large segment of Greenwood.

Still, in recent years, people have been organizing efforts to rebuild Black Wall Street, as Greenwood’s business district became known. The collective memory of what occurred in 1921 and a strong determination have inspired a new generation of business owners. Witnessing the deaths of African-Americans at the hands of police and the disproportionate rates of death and illness from COVID among people of color has sparked a need for reminders of resilience and historical context, writes Janna Zinzi in Colorlines, a daily site that features news and investigative reporting, cultural coverage, and analysis from the perspective of communities of color. “While the story of Black Wall Street and the upcoming history of the 1921 massacre illustrates the brutality of unchecked white supremacy,” Zinzi observes, “it also asserts the robust spirit of the Black community and entrepreneurship.”

Check out an endangered New Deal school building and mural. As some were making Preservation Month in May an opportunity to explore landmarks and sites, others have used the opportunity to bring virtual attention to places that may be lost, such as Preservation New Jersey’s 2020 listing of 10 endangered historic places. It is a diverse range, including a 1718 dwelling that was caught in the crossfire of the American Revolution battle at Monmouth, an 1870 Colonial Revival mansion, a 1968 portable Futuro House, and the state’s 1970s heritage of late modern and postmodern houses. All are available for a virtual look with lots of good information.

One endangered place reflects the federal government’s response in a different era to hard times, the Roosevelt Public School. It was constructed as part of the Jersey Homesteads, a community that the federal Division of Subsistence Homesteads commissioned. This division, which the federal government set up as part of President Franklin Roosevelt’s New Deal, promoted a “back to land” ethos. At Jersey Homesteads, a program brought some 200 unemployed Jewish garment workers to resettle in an agricultural and industrial community. Jersey Homesteads later separated from the surrounding township and incorporated as a borough. Following the sale of the houses from the federal government to those who settled there, it became Roosevelt Borough, named in 1945 in honor of the President who died earlier in the year.

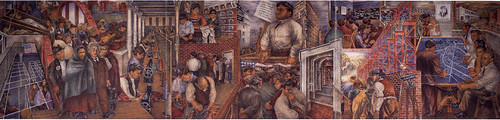

The mural by artist Ben Shahn in the Roosevelt Public School

Photo: The Roosevelt Arts Project

While various programs preserve the community and open space around it, Roosevelt Public School is an unprotected part of this heritage. Architects Louis Kahn and Alfred Kastner, who designed the Jersey Homesteads community, conceived the building as a combination school and community center.

A particularly striking, significant feature is a mural in the school by painter and muralist Ben Shahn, his first major commission. The mural depicts the lives and generations of the Jewish settlers, as immigrants arriving from Germany and Eastern Europe, then as workers in the sweatshops and participants and leaders in the trade unions, and ultimately to the development of Roosevelt, with its small factory and farms, according to the Roosevelt Arts Project. The Arts Project has an explainer describing the vivid panels and a video about the mural. Roosevelt School still operates as a elementary school, but if increasing fiscal uncertainty forces a closure, the building’s maintenance and preservation is far from assured.

Reflections

The buildings and sites that society preserves and honors speak of its values. Moreover, so does what is visible and invisible. We see this as community groups, city councils, and state governments move to take down Confederate statues and memorials. It has required an honesty about history, a crucial endeavor and not an easy one.

At a time when hundreds of thousands have died globally due to COVID, the suffering is immense. In the United States, the disproportionate deaths and illnesses among people of color have again told the nation we are failing in major ways to live up to proclamations that the Founders signed and that many have fought for. So, too, has the heinous killing of George Floyd and the brutality we continue to witness signaled these continuing flaws in our imperfect union.

It is no wonder that thousands and thousands, many of the younger generations, have poured into the streets. To face and shape our future, we need to continually confront and dig into our past, both what is to be celebrated and what is to be faced with difficulty. That is why historic preservation is about now and the future as much as the past. The value of creating thoughtful virtual experiences of historic places is more important than ever.

No Comments so far ↓

There are no comments yet...Kick things off by filling out the form below.