A year after the tragic Triangle shirtwaist factory fire in 1911, sculptor Evelyn Beatrice Longman created a memorial, commissioned by the City of New York, to the seven female victims whose remains could not be identified. The city installed the sculpture with little public attention in the Cemetery of the Evergreens in Brooklyn. This memorial wasn’t mentioned in the press, according to an article on Longman’s work by Ellen Wiley Todd in American Art magazine, nor was it ever noted in Longman’s records.

Contrast that with this week, the 100th anniversary of the March 25, 1911 factory fire that killed 146 people, mostly young girls and women from Jewish and Italian immigrant families. Throughout the anniversary on Friday, the weekend, and the spring, at least 100 commemorative artistic, educational, and civic events, from plays to musical performances to exhibits and public art, will mark the Triangle fire anniversary in New York and elsewhere. One commemoration, the Chalk project, will bring a moving remembrance of the Triangle’s victims directly to the streets and to those who walk by, as it has done for the past seven years.

Such a public outpouring was not always the case during the past century. Since 1911, New York City has witnessed a wide range of responses to the Triangle tragedy. Though the horror of New York’s largest workplace disaster before 9/11 and the investigations immediately afterward inspired thousands of workers to join together in union activism and prompted major government action to better protect workers and improve factory conditions, the public commemorations of the Triangle fire were spotty until 50 years ago. True, painters such as Victor Gatto memorialized the fire, after having witnessed it at the age of 18, in a 1944 painting that shows flames licking out from the building while a crowd watches from the street. Such expressions are different than public events, however, and in the early years some feared that too much notice paid to this fire would only incite unrest.

The long-time gaps of silence in the public honoring of the fire’s victims, however, changed dramatically in 1961, as an exhibit, “Art | Memory | Place: Commemorating the Triangle Shirtwaist Factory Fire,” at New York University’s Grey Art Gallery, details. At the 50th anniversary commemoration in 1961 in front of the Brown Building (formerly the Asch Building), which housed the factory, former First Lady Eleanor Roosevelt was a featured speaker. The International Ladies Garment Workers Union (ILGWU) sponsored the event. Survivors of the fire, firefighters, and Frances Perkins, ex-Secretary of Labor under Franklin Delano Roosevelt, who had witnessed the fire as a young woman, were among those gathered.

Annual commemorations have continued in New York each year in the half-century since then. (Part 1 of this Mindfulwalker.com series explores a walking experience of the illuminating Grey Art Gallery exhibit, which delves into the tragic day of the fire, the immediate aftermath and consequences, and the various forms of collective memory of the fire.) This year’s official commemoration, again sponsored by Workers United (formerly the ILGWU), will begin Friday at 11 a.m., with music and a procession, followed by speakers and a memorial ceremony during which children will read the names of the fire’s victims and place flowers at the original site, on the corner of Washington Place and Greene Street in Manhattan. It is expected to draw thousands of people.

The memorializing of Triangle today shows how this tragedy that ended the tender lives of so many people in a brief flash – most of them girls in their teens and young women in their early 20s – strikes something very deep in the public consciousness. The Triangle fire stays with us, 100 years after that horrible day. It is manifest in the deep and varying ways that many have chosen to remember the disaster today, from the creations of vintage shirtwaists to show the blouses that the factory workers made to public art installations that impart the memory of the victims to those walking New York’s streets.

This shirtwaist, in the style of one that would have been popular around 1911, is part of the Grey Art Gallery exhibit on the Triangle factory fire. It was sewn by Alexandra Hoffman, from the Costume Studies program at NYU’s Steinhardt School of Culture, Education, and Human Development.

Drawing and Honoring

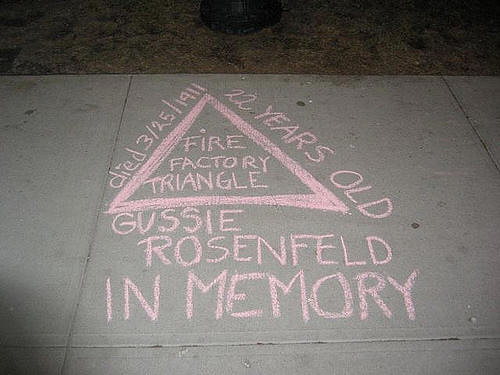

“Chalk” is, perhaps, one of the most unusual ways that people have chosen to remember this tragedy and ensure that others do not forget it. Each year, volunteers go throughout the city to inscribe each victim’s name and age on the sidewalks in front of the homes where each person lived. They mark these memorials in, as the title of the initiative denotes, chalk. In 2004, Ruth Sergel, after discovering that many victims had lived in close proximity to her East Village residence, conceived of the idea of memorializing the victims at the addresses where they had lived. She and a number of friends went out that first year and “chalked” the victim’s name, age, and cause of death. Each year, those who “chalk” continue this honoring.

This year as usual, on March 25, Chalk 2011 volunteers again will go to the East Village, Lower East Side, and other city neighborhoods to draw the memorials where the victims lived. They use chalk of pink, green, yellow, and other bright colors, as well as white; draw differing shapes such as triangles around the names; and place a leaflet with information about the Triangle shirtwaist factory fire. A sidewalk memorial reads, “RIP, Beckie Neubauer, 19 years old, Lived 19 Clinton St., Died March 25, 1911, Triangle Factory Fire.”

What started as one woman’s idea and a group of friends inscribing memorials has grown into a coalition movement. Sergel founded the Remember the Triangle Fire Coalition, which brings together more than 200 organizations and is spearheading and putting together a list of the events citywide and elsewhere commemorating the Triangle fire. Since 2006, Sergel and the Chalk project have also documented their memorials through digital images, which are part of the Grey Art Gallery exhibit on the fire. Seeing the chalked writings makes the victims come very alive in one’s imaging: How long did she (or he) live here? What were their thoughts as they walked to work each day? What did they do on these streets once they came home from their long days at work? How long did a family stay here after the loss of their loved one?

Photo Credit: Street Pictures © All Rights Reserved

For those who do not have the opportunity to view the memorial chalking in person on March 25, the Grey Gallery exhibit provides a way to view a portion of it and grasp the loss of those lives. In the exhibit text, Sergel, a native New Yorker, artist, activist, and filmmaker who uses technology to empower community, says the chalking memorial has had an immense impact on her: “There’s something about physically, literally, engaging in the New York streets. And it changes you: Once you’ve chalked in front of a building, you remember that building for the rest of time. You remember it held someone’s life.”

Events and Resources: Triangle Factory Fire

Grey Art Gallery Exhibit

Exhibit at the Grey Art Gallery, New York University: Art | Memory | Place: Commemorating the Triangle Shirtwaist Factory Fire

The exhibit is on view at the Grey Art Gallery until March 26, and then will return from April 12-July 9, 2011.

Events and Resources: Remember the Triangle Fire Coalition

Remember the Triangle Fire Coalition

The Remember the Triangle Fire Coalition has an extensive listing of events for the 100th anniversary of the fire. It also offers information, many resources, and ways to get involved.

Web Exhibit: Remembering the Triangle Fire

Remembering the Triangle Factory Fire

This online exhibit of original documents and other resources offers an in-depth and moving way to explore the fire and its aftermath. It lists the names and ages of the victims, contains survivors’ interviews, and has photos and illustrations. The project presents original documents and secondary sources on the Triangle Fire, held by the Cornell University Library. They are housed in the Kheel Center for Labor-Management Documentation and Archives at Cornell University’s ILR School.

This is such a reminder that life is a gift and can sometimes be so so short.

Some define immortality as when those who have died are remembered, whether it’s day to day, year to year, or every hundred years.

We are so charged to honor the memories of those before us, selectively perhaps, for as long as we can to that end. The recent and historical memorial events for these young women are good examples of that homage.

Thank you, Suze, for also providing me with the opportunity to pause and celebrate their lives…their memory.

What a wonderful, well-researched, and well-written post. Bravo from another writer who knows how much work went into this.

Michele,

Thank you so much for your kind and affirming comments. I appreciate that!

I always love hearing from writers who know what goes into a particular piece of writing, especially when it’s carefully done. I was recently quoting William Zinsser in a workshop I teach on writing: “If you find that writing is hard, it’s because it is hard.” I find that comforting.

Bravo to you, too, for writing (and I’d welcome an opportunity to hear about the writing you do).

Again, thanks,

Susan

Lynne,

In the lives of those 15-year-olds and 20-year-olds who succumbed in that terrible fire, in a quick flash, is such a reminder of the preciousness of our days. The definition you cite of immortality is a beautiful one…people live in our memories, images, and the continuing soul of our own lives.

I do think, as you say, that reaching out to remember these victims, so many of them young girls and women, is a way to honor them and keep alive their spirits. Often, when I think of this fire, I like to think of them in the days before, perhaps laughing with their friends or chattering excitedly about something together. When I see their names, that is what I see and think of, as well as the tedious and tough work they did and the tragic way in which they died.

Thanks for your thoughtful comment!

Susan